As a third-grader in Ithaca, New York, I picked up a book by the great American poet A.R. Ammons. I opened it, not because I was interested in great American poetry, but because the poet’s son, John Ammons, a towering fifth-grader, was the school’s best basketball player. I wanted to be more like John, and thought that maybe his father’s poetry could help.

I found a poem that had a promising title and seemed mercifully short:

Spaceship It's amazing all this motion going on and water can lie still in glasses and the gas can in the garage doesn't rattle. |

The poem didn’t sound the way I expected poems to sound. It sounded more like a normal person, maybe even a kid, talking. The words were arranged on the page in unusual ways, but they were saying ordinary things. Indeed, my family had an old metal gas can in our garage — it would rattle when you moved it, but it didn’t often move. Why did the poem claim that was “amazing”? And why was the poem called “Spaceship”? And what did any of this have to do with improving my jump shot?

I asked a teacher. She read the poem, read it again, and asked me a few questions that amounted to “what if the spaceship were the planet Earth, hurtling through space at 18 miles-per-second, even as our own local world seems still?” I stared at her, my mind hurtling on its own orbit from the page, to our garage, to outer space, and back to the page. I never looked at the gas can in my garage, or water in a glass, or a picture of the earth in space, or poems in books, the same way again. I became interested in experiencing “all this motion going on” in a poem as well as the clarity that “can lie still” within, waiting for us to drink it.

My jump shot still has not graduated from elementary school, but my joy in poetry keeps growing.

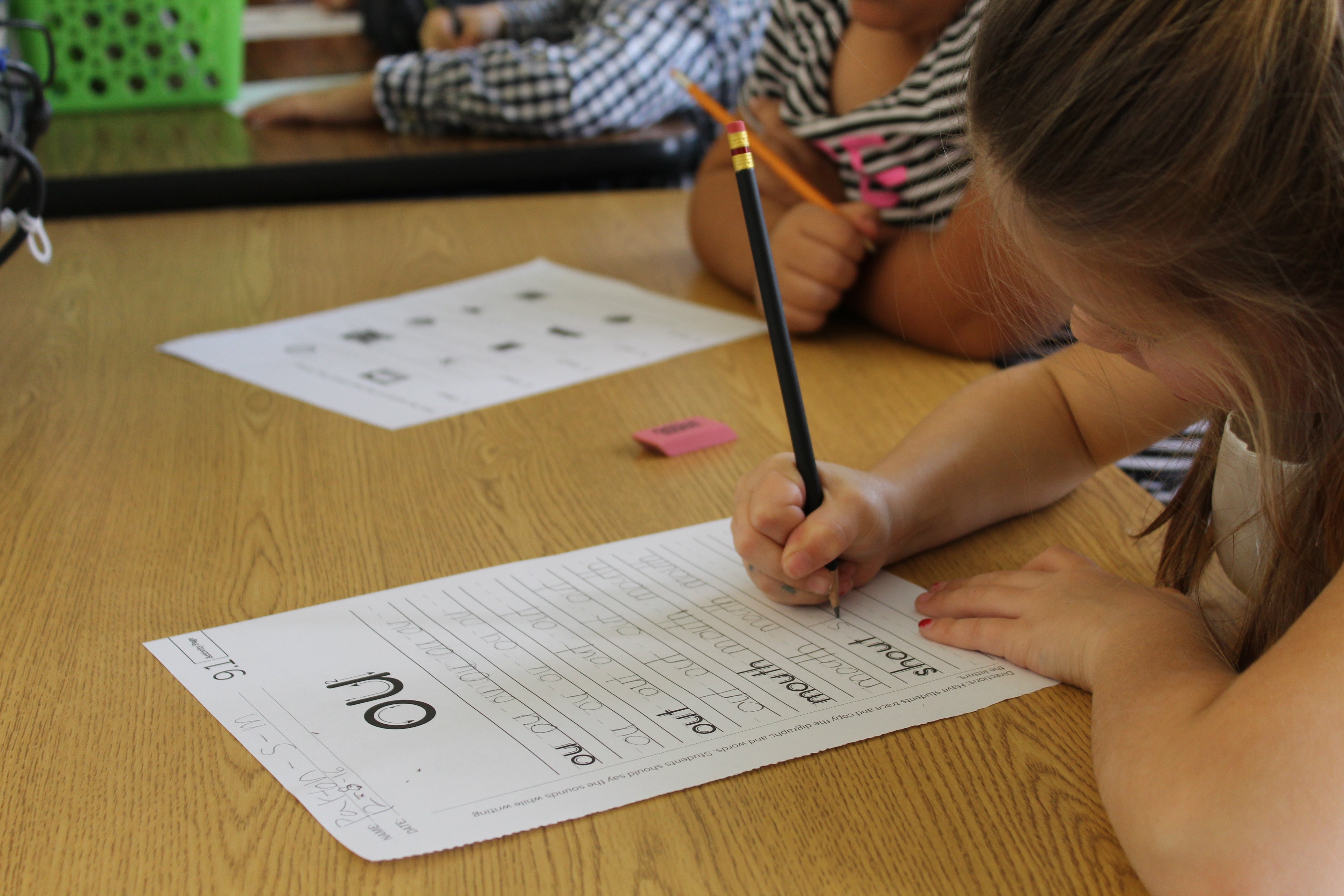

The researchers who study how to create more “joy” in learning would point out that my moment of discovering the joy of poetry had several features:

- Process and product. I went through a period of struggle and confusion.

- Freedom/autonomy. I chose the book and the poem; it wasn’t assigned to me.

- Community. My “aha moment” came in close interaction with a teacher. Plus, the poet—and more importantly, his son—lived in my neighborhood.

- Personalization. It all started with an interest I already had (basketball, spaceships).

These are four of the staple ingredients of creating joy in the classroom. Teachers have an intuitive feel for them—and increasingly, there is cognitive science backing for these intuitions.

Of course no one sets out to reduce the amount of joy in the classroom. There’s no movement to limit lesson plans to rote memorization, or to make classroom bulletin boards less cheerful. But in all the pressures and complexities of teaching, it is easy for joy to be sacrificed. The tools and modes of teaching have changed and expanded in recent years; we should find ways to create new and more expansive forms of joy.

That’s what we’re exploring in this issue, with an excerpt from Why Don’t Students Like School? by cognitive scientist Daniel T. Willingham. Ph.D., some thoughts from teachers about how they make sure they enter the classroom with their own “joy reserves” full, plus a few fundamental thoughts and questions that I’ll offer here.

It’s important to define what we do and don’t mean by “joy” in the context of a classroom. Is joy synonymous with fun? No. Fun and joy at school are related, but not interchangeable. Sean Slade, director of outreach at ASCD, making the case for fun in learning, rightly asks: “Why do we assume that learning occurs only when kids are serious and quiet?” But I think we should assume that joy can occur when a kid is serious and quiet. When I read Ammons, I didn’t whoop and dance on a table. My joy was serious and quiet. I think it’s important that we recognize, and cultivate, experiences of joy not only as explicit expressions of pleasure, but also as connection, satisfaction, flow.

So how do we encourage and maximize that? What conditions can teachers create for joy to flourish?

Process and product. In “Ten theses of the joy of learning at primary schools” (Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 182, No. 1, January 2012, 87–105), Taina Rantala and Kaarina Määttä, Ph.D., say that the experience of joy in learning is enhanced by student effort to learn and the “emotion of achievement that results from persistent work”—that is, “both during the learning process and after the process due to achieved results.” There’s joy in hard work that pays off. This is related to Carol Dweck, Ph.D.'s growth mindset, which encourages teachers to help students believe that hard work pays off (vs. “I’m just bad at reading”). The growth-mindset approach—which we know boosts achievement—could also help students find joy in the short and long terms by helping them thrive on both challenges and setbacks.

Freedom. Simply: “joy is linked with freedom” (Rantala & Määttä). It’s possible to increase the sense of freedom in a classroom not only by including some unstructured time and activities, but also by offering students opportunities to make small and incidental, but liberating, choices during the structured time: choosing a partner, a place to sit, a certain color of marker. Rantala & Määttä: “For adults, it makes no difference whether we write on red or blue paper, but when a student can choose between these options, there will be a lot of joy in the air.”

Community. Of course the joy of learning and discovery can be solitary (like the joy I felt upon seeing that the gas can in our garage also did not rattle). But communal experiences—a shared joke, solution, or eureka moment—are said to both emerge from and enhance joy in the classroom community. As neurologist and educator Judy Willis, M.D., M.Ed. wrote in Research-Based Strategies to Ignite Student Learning: Insights from a Neurologist and Classroom Teacher (ASCD, 2006): “‘Aha’ moments are more likely to occur in an atmosphere of ‘exuberant discovery,’ where students of all ages retain that kindergarten enthusiasm of embracing each day with the joy of learning.”

Personalization. Teachers can create the general conditions for joy all day long, but will they work for everyone? Just as we personalize learning, we can personalize joy. Not everyone will dig poetry the way I do; one person’s delight is another’s drudgery. This is a matter of experimentation and observation around what makes a given student light up.

Indeed, that can be an end in itself. Observing students’ bursts of intellectual joy—those moments of pure delight in engagement and revelation—is at the heart of what can make teaching thrilling. The pursuit of joy in the classroom can itself be a source of joy, even when some attempt doesn’t work and mistakes are made. But the biggest mistake, perhaps, is to not notice a small moment of joy, or even—as Rantala and Määttä warn—unintentionally send it away: “[J]oy can be found through many efforts and mistakes by self-experimenting and doing. The joy of learning consists of little, evanescent moments. It may not blow up galaxies, but is accessible to every little and big learner. A teacher has to act in such a way so as not to drive it away unobserved.”

Share this post

.png)